The objective that started it all

This morning a new client, one that engaged us to ensure they were getting the most out of their OKRs program (something we hear a lot by the way…why do organizations sense they’re not getting the most from OKRs? Hmmm….I smell a future blog post), sent over a batch of OKRs for me to review, including this objective from their IT department:

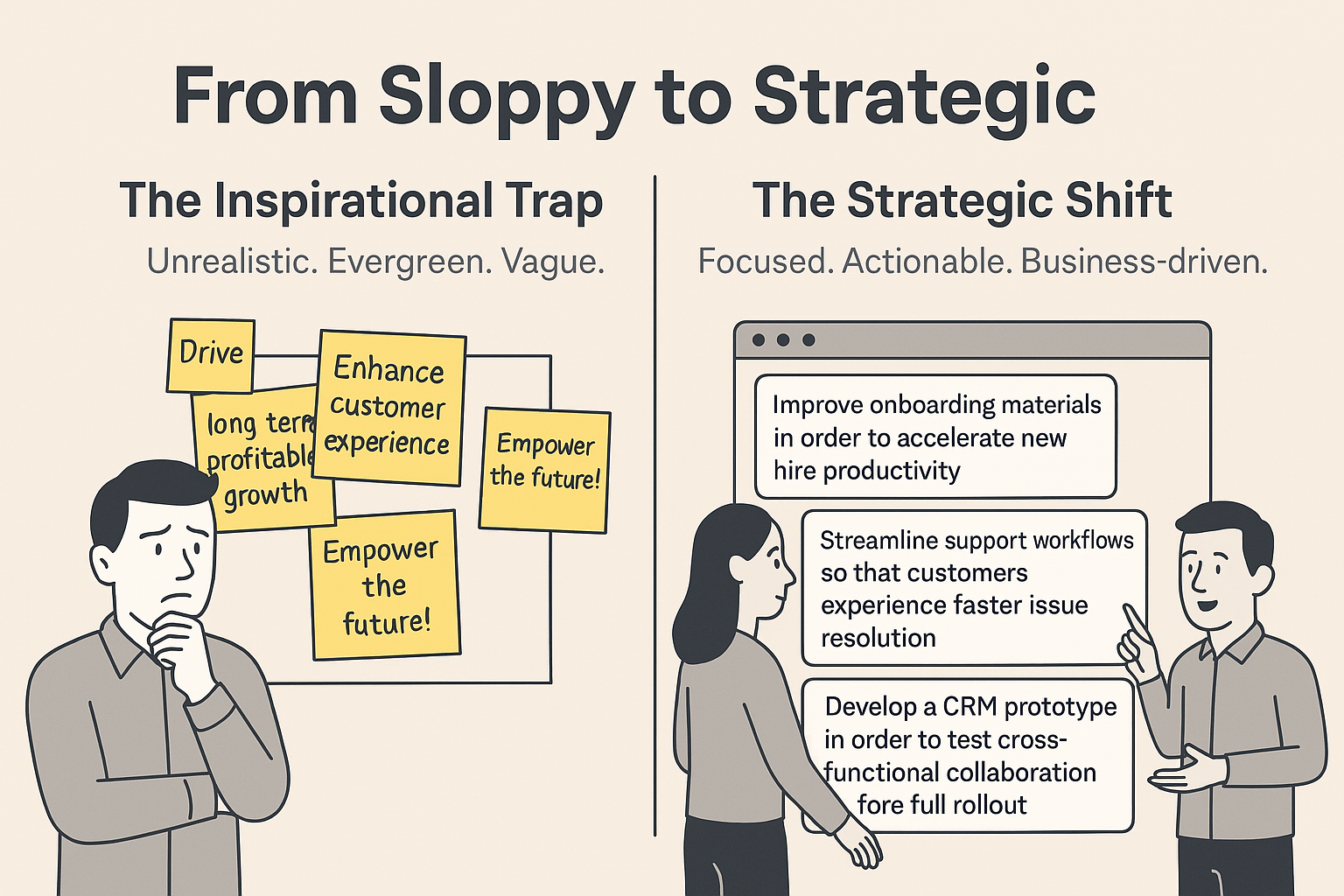

Develop solutions that enable long-term, profitable growth while enhancing the customer experience.

The first thing you should know is that this is a quarterly OKR. Does that raise any alarm bells for you? It certainly does for me. Is it realistic to expect this IT group – which like most IT departments toiling in every company around the world is undoubtedly struggling under the crushing weight of current tech and user demands – to drive growth that is long-term and profitable AND enhance the customer experience in ninety days? The short answer is no. This is an example of something I see playing out frequently in OKR land – groups creating overly ambitious OKRs which if measured using appropriate key results have pretty much zero percent likelihood of achievement across a single quarter.

Another problem with this objective is that it’s what I term “evergreen.” By that I mean it could apply and be used every quarter between now and the end of time. Would there ever be an occasion when this team would not want to deliver solutions that drive long-term, profitable growth and enhance the customer experience? Of course not. It’s part of their core value proposition, their raison d’etre. If they do choose this objective right now, in the current quarter, what are they going to do next quarter, solve world hunger? If I’m being harsh it’s only because I have seen the power of OKRs in action at organizations around the world, but I know that power can only be exploited through the creation of strategic, realistic, and technically-sound objectives and key results.

Why do sloppy objectives get written?

So, how do objectives like this get written and approved in the first place? My guess, based on work with hundreds of organizations over the years, is that some combination of the following was at play:

- The group received no, little, or inappropriate training in the mechanics of writing strong OKRs. One of the very seductive benefits of OKRs is the framework’s simplicity – everyone loves that about OKRs. But – huge cliché coming – simple doesn’t mean simplistic. We spend hours in our training sessions hammering on the fundamentals of writing effective OKRs because the only way you can generate the benefits of focus, alignment, and engagement is from starting with the discipline (yes, discipline) of writing technically-proficient OKRs.

- Somewhere along the line, whether in the little training they did receive, or based on something the team leader read some place, it was determined that objectives must be inspirational. I have heard quotes such as the following literally dozens of times during OKRs workshops: “That’s a good objective…but it’s not inspirational enough!” Quick, everyone dust off those 1990s Successories posters for some inspiration on inspiration…”Challenge: It’s not the mountain we conquer, but ourselves!” That’s more like it, right – now let’s apply that to our objectives. WRONG! There is no doubt that inspiration is important but you have to be flexible in how you define the term in your context. Inspiration in the objective realm should connote something the team feels is a legitimate challenge, but with focus and determination is achievable, and they’re willing to put in the necessary effort to make it happen. What it doesn’t have to be is something you’d find inside a greeting card.

- The objective was agreed upon as part of a poor consensus and prioritization process. This happens all the time – during the workshop a number of objective ideas are bandied about, all are captured in Miro or on a white board, and upon reflection they all look really good. Achieving any of them would definitely have an impact on the group’s ability to deliver. But, actually grinding down on the hard work of prioritizing and selecting just one is too much to ask, and so after a lengthy period of silent frustration someone offers this: “What if we combine them into one!” Everyone looks around and another person weighs in with “That could work.” A little bit more head nodding, shuffling of sticky notes, and the next thing you know you have an objective like Develop solutions that enable long-term, profitable growth while enhancing the customer experience. Cut! Print! Moving on.

How to shift from sloppy to strategic

This situation is easily avoided by following some basic advice. First of all, if you find yourself with an objective like our example above remind the team that it’s a good start – you’ve identified something everyone feels passionate and excited about, that perhaps could represent a year-long vision or theme you can rally around. But you must emphasize that for the purposes of OKRs, it’s just too grandiose for one ninety-day cycle. Then start deconstructing it, take it apart piece by piece. If you ultimately want to get to the end state described in the objective, what is the very first thing that needs to achieved? What’s the second, and the third. Once you have a sequenced list you probably have OKRs lined up for the next several quarters. And the good news keeps on coming – the tighter and more specific you make your objective, the greater the chance you’ll develop realistic and outcome-based key results that demonstrate real progress toward the end goal.

Remember, writing effective OKRs isn’t about cramming big ambitions into a single quarter—it’s about setting the right focus at the right time. A well-crafted OKR should challenge your team while remaining achievable, serving as a stepping stone toward larger goals. By trading vague aspirations for precise, time-bound objectives, you can turn OKRs from a frustrating exercise into a powerful tool for progress.